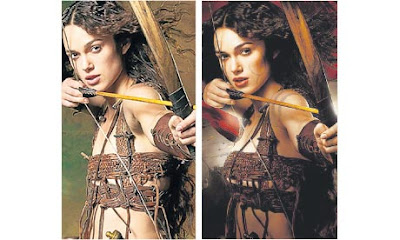

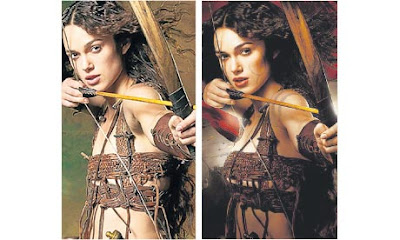

A few years ago I had heard rumours that a certain film had spent an obscene amount (apparently millions) on having to clean up images of Keira Knightley post filming as there were apparently issue with her skin complection. Recently I stumbled across Charles Arthur's brilliant 'How we Learned to Love Photoshop' article which had an example of a Keria Knightley before and after.

Recently I have been more and more aware of an increasing number of Photoshop/airbrushing related articles in the mainstream media. In The Word magazine earlier this year I saw a great article that I've been trying to get my hands on by Andrew Harrison which showed some fantastic examples of airbrushing. One image which is particularly memorable that I have managed to retrieve from Google is the image of a shark attacking a military helicopter which was released in August 2002. Initially people did believe that the image was real, but it did later transpire that it was infact two seperate images skillfully Photoshopped together.

Charles Arthur enlightens his readers with the history of Photoshop saying, 'Photoshop has, like Google, transcended its origins in the world of computing, and become a verb. But whereas "to Google" is almost always used positively to express usefulness, Photoshopping is almost always a term of abuse: "That picture was Photo shopped" has become a shorthand way of saying it is untrustworthy and misleading...

...But it was Photoshop that made altering images routine. It began circumspectly as a program written by Thomas Knoll, who, in the autumn of 1987, was doing in a PhD in computer vision but for fun wrote a program to display images with grey in them on a black-and-white monitor. Knoll called the program Display, writing it on his Mac Plus computer. Then his brother John, who worked at George Lucas's Industrial Light and Magic company, which did the visual effects for the Star Wars films, noticed its potential. They collaborated, bought a Macintosh II – capable of displaying colours! – and set to work; the program's name mutated until they hit on Photoshop.

In September 1988, Adobe Systems signed a licence to distribute it – wisely, the Knolls took a royalties deal that made them very rich. And on 19 February 1990, Photoshop 1.0 became available. At the time it fitted on to a single floppy disk – nowadays it takes a DVD – although it had, even then, fallen foul of piracy after the Knolls demonstrated it to some Apple engineers, who "shared" the demo disks that were left behind with a few hundred of their closest friends. Nowadays, Photoshop is reckoned to be one of the most pirated programs in the world, behind Microsoft's Windows. Its high price – around £560 – is indicative of the fact it has no real rivals.

Photoshop quickly became embedded in computer culture. Apple would try to prove its computers were faster than those running Windows by holding "Photoshop bake-offs" during Steve Jobs's keynote addresses: a Windows machine and an Apple one would run through an automated process to tweak and manipulate an image in exactly the same way. Oddly enough, the Apple machine always won.

Photoshop has even created its own two-player sport, "layer tennis". The first player "serves" an image: the opponent then alters it and sends it back; the first player continues the process. Done in public, with commentary, it takes on its own strange allure.

Do not, though, expect to join the ranks of elite players immediately. Seeing Photoshop running on a computer is like viewing the cockpit of a 747; what, you wonder, do all those buttons do? Many experts say they have taught themselves how to use it over a decade or more. Creative technology consultant Richard Elen describes it as less like flying a plane, more like dealing with a huge house – some people never visit all the rooms. "I probably use 50%-70% of what the apps can do," Elen says. "There are features I seldom, if ever, use. Others I use all the time – clone tools, for instance [which copy an item inside an image] – and I think I'm fairly adept at them."

Russell Quinn, a computer scientist and self-taught Photoshop user, says it's "akin to picking up a guitar for the first time. The whole world is there for the taking, but it's difficult to get started." He thinks two years is a reasonable timescale to get on top of it.

Steve Caplin, who has done photomontages for the Guardian for 20 years, recalls his first use of the program: "An illustration in Punch of the Queen. Photoshop was very much simpler then, but it had real power." He too has featured on the Photoshop Disasters blog – "A missing shoulder on the cover of my book, ironically called How to Cheat in Photoshop!" – and says he feels real sympathy for those who have run into trouble with the program.

"It's all too easy to overlook something that's then blindingly obvious when it's printed. It's just like spelling mistakes in print, really." ' (Charles Arthur)

There are Blogs out there which cover the good, the bad and the ugly of Photoshopping/airbrushing. Photoshop Disasters in particular does bring a big smile to my face when looking at some of the extreme examples and humorous comments attached, a nice bit of morning viewing to get my day started with a smile!